The Colonies

History of the Colonies

that used to travel to/from to Cuba,

bringing a cargo of almost 4,000 children

to Southampton Docks, 23rd May 1937

The Spanish Civil War was a bitter conflict, which divided the nation. Even now, the Spanish people are still learning to come to terms with their past which saw tens of thousands of deaths and millions uprooted and destitute. The plight of the Basque people was particularly tragic following the bombing of the town of Guernica in April 1937 by the planes of the Nazi Condor Legion.

The destruction of Guernica, which inspired Pablo Picasso to paint his masterpiece of the same name, also brought nearly 4.000 children to Britain as refugees from the Spanish Civil War. Public opinion was outraged by the bombing of Guernica, the first ever saturation bombing of a civilian population. The Basque government appealed to foreign nations to give temporary asylum to the children, but the British government adhered to its policy of non-intervention.

The Duchess of Atholl, President of the National Joint Committee for Spanish Relief, took up the campaign to urge the government to accept the Basque children and finally, permission was reluctantly granted. However, the government refused to be responsible financially for the children, saying that this would violate the non-intervention pact. It demanded that the newly formed Basque Children's Committee guarantee 10/- per week for the care and education of each child.

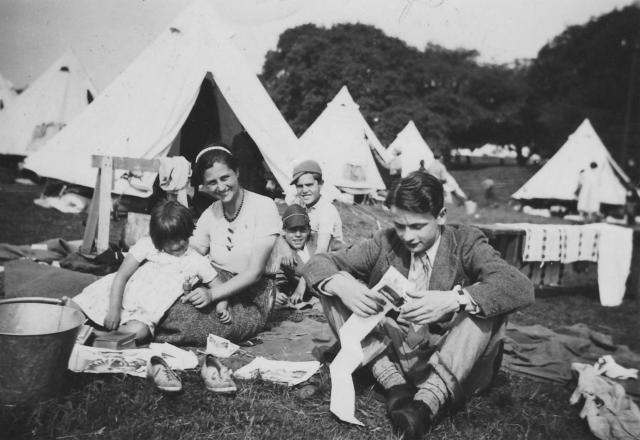

at Stoneham Camp

The children left for Britain on the steamship the 'Habana' on 21st May 1937. Each child had been given a cardboard hexagonal disk to pin on his clothes with an identification number and the words 'Expedición a Inglaterra' printed on it. The ship, supposed to carry around 800 passengers, carried 3840 children, 80 teachers, 120 helpers, 15 catholic priests and 2 doctors. The children were crammed into the boat, and slept where they could, even in the lifeboats. The journey was extremely rough in the Bay of Biscay and most of the children were violently seasick

The steamer arrived at Southampton on 23rd May. Thousands of people lined the quayside and the children, in spite of their ordeal, were excited, thinking that the bunting that was up everywhere was to celebrate their arrival: later they learned that it had been put up for the coronation of George VI which had taken place ten days earlier!

They were sent in busloads to a camp at North Stoneham in Eastleigh that had been set up in three fields. The setting up of the camp in less than two weeks was the result of a remarkable effort by the whole community: volunteers had worked round the clock and all through the Bank Holiday to prepare it.

(Ana Maria Gonzalez)

at Stoneham Dated Sunday 30th May

The children were completely unprepared for camping: the majority had lived in densely packed flats in the working class districts of one of the most industrialised city in Spain. In fact, many of the children did not stay there long: the idea was that they should be dispersed in homes or ‘colonies’ as soon as possible. The first to offer asylum was the Salvation Army, who undertook to take 400, followed by the Catholic Church, who committed itself to take 1,200 children. Little by little, from the end of May, and during the summer, the children left the provisional camp in groups to go to other homes situated all over Great Britain and staffed and financed by individual volunteers, church groups, trade unions, and other interested groups.

By mid-September, all had been relocated to residential homes throughout Britain. After the fall of Bilbao and Franco's capture of the rest of northern Spain in the summer of 1937, the process of repatriation began. By the start of World War II in 1939, most of the children had left for Spain, although for some of the children this was a terrible ordeal.

at Stoneham Camp

Some didn't speak Spanish, others had forgotten their parents. They couldn't get used to the restrictions in Spain. The 400 or so who remained in Britain either chose to stay (if they were over 16, they were given the choice), or had to stay because their parents were either dead or imprisoned. By 1945, there were still over 250 in Britain and many of these settled permanently, sometimes marrying local people and remaining in Britain for the rest of their lives.

Further details on the Spanish Civil War, the bombing of Guernica, and on the Basque children are available at www.international-brigades.org.uk.